Words by Bengi-Sue Şirin

Wednesday 8th June 2022 is the day that Paula Rego died. I love her work; its cynical slant on society; the cartwheels it dances over norms and expectations; the incorporation of humour in unexpected ways, in the darkest of places. So to end Wednesday 8th June seeing Gecko Theatre’s show The Wedding feels like an apt homage to ideas that fascinated Paula Rego. Gecko’s programme notes describe the piece thus:

The Wedding is inspired by the complexities of human nature: the struggle between love and anger, creation and destruction, community and isolation. In a blur of wedding dresses and contractual obligations, our extraordinary ensemble of international performers will guide audiences through a dystopian world in which we are all brides, wedded to society.

I can’t help but think of Rego’s magnificent 1994 painting ‘Bride’, an arresting part of her Dog Women series. It strikes me because the bride, attired in white for what society tells us is ‘the best day of our lives,’ looks so remote, so inexplicable. So much the figure of the complexities of human nature. I find it a compellingly jarring reframing, when the wedding becomes a symbol of struggle, discontent or oppression.

This theme is in keeping with Gecko’s artistic vision. They are an Ipswich-based physical theatre company who, in their words, ‘create performance that explore contemporary themes relevant to the society in which we live, performance that is inspiring and provocative.’ Under the leadership of Artistic Director Amit Lahav, Gecko have performed their 7 shows and 2 films at venues all across the world, from the Fringe to the stage to the GCSE Dance syllabus. I have not come across any of their work before tonight but I see that Gecko have a buzz about them – the audience at Barbican Theatre are for the most part a young, hip, Peckham Levels crowd. And with disco music in the background and smoke filling the auditorium, it almost feels like I am at a bar. The Wedding is back by popular demand after a highly popular 2019 run. How many non-establishment stage shows can say that?

The lights dim. When they come back on, we see a white dress hanging centre-stage, and what looks like the end of a giant cylinder slide pouring onto some cushions downstage left. Kind of Louise Bourgeois meets Tracey Emin? Out of silence we hear rapid gleeful cries, cleverly ricocheting from side to side – and then I realise, it is somebody whizzing down the giant slide! Moments later, a man shoots out of the chute. Other dancers enter this way, too. The audience are delighted, I can feel the thrill in the air. Tonally, it is playful, madcap, avant-garde. I am hooked.

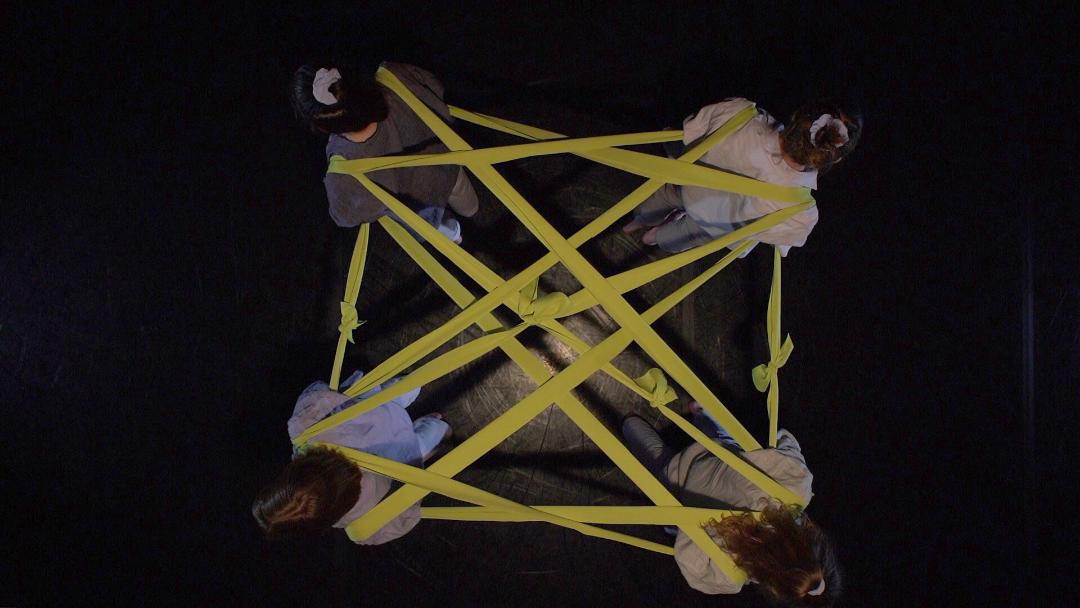

The Wedding to me is a series of vignettes linked by an overriding theme, ricocheting from side to side like echoes from a giant slide. It is one of those dance shows where I best conceptualise it through moments. One of these moments near the beginning which is etched onto my memory is where a woman is bepuppeted by four male dancers around her. They use sticks and a square of white fabric to ingeniously cover her like those parachute games we used to play at school, lifting and rotating it above her. At points, she stands on top of it, and the men pull at it with sticks to make it appear like she is floating. The fabric alternates between a lightness that floats above her, to an oppression that pulls her down. We hear a riot of Balkan brass, music you would hear in the polka tent. Confetti falls in piñata-fast bursts, like it will do for much of the piece. The fact that she wears a wedding dress sharpens the knives that carve this imagery – of a woman happy, or of a woman trapped.

Another moment I found really engaging was the suitcase scene. The stage was empty apart from a lone suitcase. Just as I was starting to wonder, how do I unpack this image, a real live MAN popped out. The way he did it conveyed that the suitcase was his home, and that we had disturbed him but he would be happy to entertain us for a bit. This man – Mario Patrón – is a master of physical theatre. He moves in the manner of a cartoon lizard (or gecko) with agile, sideways comedy. Patrón retrieves a radio from his suitcase-home and props it up on top, playing a lively track to accompany his dancing. He speaks all the while, a mix of his native Spanish and the kind of English that a street performer uses to tempt tourists into stopping and watching. I realise that that is exactly what he is doing; there is a hat in front of him, he has the charm and the moves… Then out of the suitcase-home pops a woman, danced by Wai Shan Vivian Luk. She chatters lovingly to him, but it is not in English or Spanish… It is in her native language? Despite the different dialects, the two clearly establish a relationship for us all to see. I am amazed that I can form a storyline out of such aural chaos, but the strength of the choreography and the dancers is such. This particular scene is really sweet and personable – perhaps a positive angle on matrimony? But, I later realise, it’s actually setting us up for a harder fall when Patrón undergoes horrific violence at the hands of a violent thug in a bridal dress, unhelped by the state and left nearly for dead. Many interpretations could be made of this storyline, but for me, the institution of marriage is shown to victimise otherwise happy people. It is brutal, but a point very well made.

I realise as I write this that light, comedic moments in The Wedding arc to really dark places. Picture this – three suited and booted men, packing themselves into a very small booth that resembles a room, in the centre of a large stage. The booth has windows and what looks like furniture inside. The scale, the motivation… It is bizarre and funny. But then one of the men out of nowhere cries, “I’m struggling to breathe!” He clambers up, jolting through what would be the roof of the booth in desperate thrusting escape attempts. He begins to choke, strangled by the confines of his tie, again unhelped by the people around him. Voiceover assumes his inner narrative, repeating, “I’m struggling to breathe” over and over until…. Deadpan, droll, and in reference to the metaphorical wedding we find ourselves trapped in with society: “I want a divorce.”

So the parallels with Paula Rego are certainly there. Society, the state… They are portrayed as oppressive, violent, life-ruining things. We see the despair Patrón and Luk are left in after his attack as they hug like they have nothing left but each other. This moment, toward the end of The Wedding, marks a turning point. A single warm pink light illuminates the stage as the rest of the cast, in roles of victims rather than oppressors, wander onstage and form an even bigger hug around them. The damage done by the state is healing through people taking care of one another. After all the show’s fanfare and noise, this scene is stripped back and beautiful; the acoustic album. Even the simplicity of the circle formation suddenly appears transcendental. And now too there is confetti – but much less, and much more gently – soft and wayward, like falling petals. From this point, the pinky lighting toughens to a much more fierce and fiery orange, and the ensemble ride the wave of the collective to take their seats on a horizontal line of chairs. For what I now realise is the first moment of total unity in the piece, they clap their hands, stamp their feet, and chant their newfound group strength in a rousing, upbeat rhythm. It surges, more and more intense – and ends, triumphantly, the kind of ending that you can’t help but love and applaud furiously. All the brutality and darkness was harrowing, but it brought us here.

The Wedding whizzes us down a gigantic emotional slide – starting at silliness, looping through playfulness and charm, taking us to the depths of state brutality and the oppression of the individual, and then giving us a final push down the tunnel of collective healing and catharsis. The interval-less 80 minutes fly by, which for me, is rare (I value my processing time). Indeed, ‘The Wedding’ does not have the ease-to-follow of linear narrative. It is much less like a three course wedding banquet than a lively buffet affair, where you have much more freedom over your helping and you can individually choose which hors you’d most like with which d’oeuvres. And I feel this is extremely pertinent to the idea of the piece. Life, as dictated and interpreted by oneself, as much more affirming than that to which the state would have us wed.